Five glorious days musing over fascinating eighteenth and nineteenth-century objects and texts, multiple delectable meals (including one cooked over the hearth at Old Sturbridge Village!), stimulating conversation, and umpteen new friendships and professional food studies connections. All this was the result of my incredible experience at the American Antiquarian Society in the Center for Historic American Visual Culture (CHAViC) seminar, “Culinary Culture: The Politics of American Foodways, 1765-1900,” which was organized and orchestrated by Nan Wolverton, CHAViC Director, and led by Nancy Siegel, Professor of Art History, Towson University.

The week’s lectures, material, and discussions were oriented around a case study assignment, in which each student chose one of seven artifacts/objects/ephemera (pictured below) to discuss in greater detail.

With such exciting options, we all agonized over which object to choose and spent the week working through questions grounded in the lives of the objects themselves, like:

- Where did it come from?

- Who held it, used it, or owned it?

- Where did it live? Was it meant to be private or public?

- Why was it made? What is its message?

- What does it tell us about the time period in which it was produced?

- Who would buy it?

After much flip-flopping, I finally settled my attentions on the Ridgway plate depicting the Insane Hospital, Boston, c. 1825. Drawn to the question: “Why does an image of a hospital for the mentally ill grace the bottom of this plate?”—I organized my thoughts around the plate’s production, consumption, and representation, an exercise that merged my interests in food studies, the history of medicine and public health, and everyday objects and popular culture.

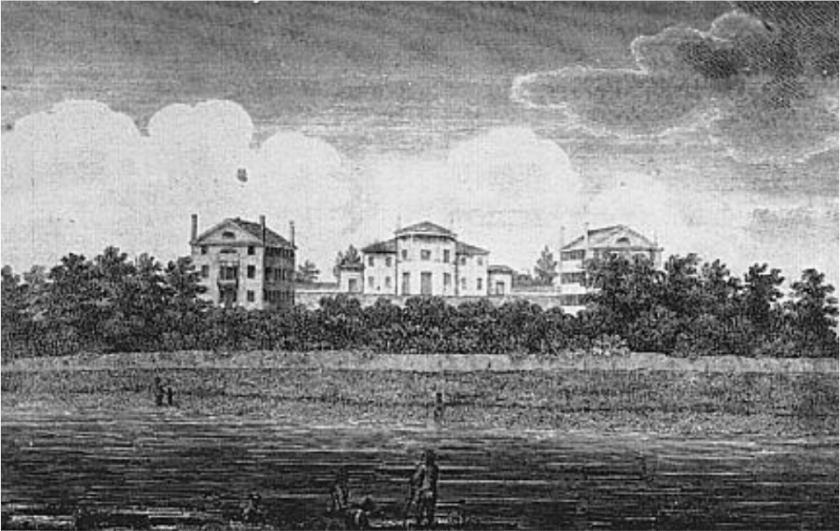

John & William Ridgway, Insane Hospital, Boston, c. 1825, Beauties of America series, Staffordshire ceramic, 7″ plate

To begin with the producers, John and William Ridgway were third-generation potters, who joined and later inherited their father’s business. They both visited the United States numerous times, including a trip in 1822 on which John Ridgway kept a diary of the sites he visited, many of which made their way onto Staffordshire ceramics as part of the Beauties of America series.

Items in the series would have been collectable as individual pieces that would form a culinarily rendered guidebook to notable American sites. The hospital on this plate was opened as the “Asylum for the Insane,” a division of the Massachusetts General Hospital, in October 1818, so it’s likely Ridgway saw it in person on his trip and decided to include it in the Beauties of America series. (See below several pieces from the American Antiquarian Society’s collection of the series. Make sure to check out their gorgeous online exhibition too!)

A businessman of means, Ridgway wrote of the impressive architectural achievements he toured, describing the buildings as “fine,” “large and handsome,” “beautiful,” “magnificent,” “elegant,” and “splendid,” comments indicative of his own class status and cultivated tastes. Such observations were also fitting for the Boston hospital featured on this plate. It began as Joseph Barrell’s home, which was heralded as:

The most outstanding private residence built in America during the last decade of the [eighteenth] century.

The building was also a technological and industrial feat for its heating and ventilation systems, attributes that Ridgway commented on at similar sites. Ventilation in particular was considered a central component of disease treatment and wellbeing, in part due to medical paradigms of the time and understandings of disease transmission before the acceptance of germ theory.

But as a devout Methodist, Ridgway was also particularly interested in (and critical of) the institutions he visited that traded in Benevolence: churches, hospitals, asylums for the deaf and dumb, and as we see on this plate, asylums for “lunatics.” As such institutions combined or shifted their funding mechanisms from charity to fee-based services, Ridgway was unimpressed. For example, after touring the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, he remarked,

So far as I could see, the thing wants the inspection of regular Benevolence; the people here are too much alive to getting money and these public institutions are neglected.

And so I argue that perhaps this plate’s design, and ones like it, were selected not only to feed an American market need to gaze upon and collect itself, but also because it aligned with the values and worldview of the leadership involved in its production. As an architectural achievement and a benevolent institution, this Boston hospital for the insane was deemed socially, morally, and economically valuable by John Ridgway.

For consumers, on the other hand, this plate and its design produced value for other reasons. At the time, it wasn’t unusual for citizens to visit and tour institutions like asylums for entertainment, enlightenment, and community engagement. A consumer good, the acquisition of the plate itself also placed the buyer within the trans-Atlantic consumer culture. Forged in British clay and donned with an American scene, this plate and items like it were transnational objects, located in an identity narrative connected to the old country and to the building of a new national identity.

As such, its design might have evoked place-based pride at multiple levels. For starters, the aesthetic and moral achievement of the hospital was a decidedly American beauty, one inviting a celebration of the national. It also stands as a beacon of local and regional innovation, embraced within the context of increasing sectionalism. Notably, this hospital was the first in New England and only the fourth institution for the mentally ill in all of the United States. Furthermore, the architectural significance of the estate, designed and later greatly added to by Charles Bulfinch, also stands as a local and regional achievement.

Furthermore, in the early decades when institutions like asylums were first being constructed, removing the “insane” from prisons and placing them in more comfortable and kind surroundings might have been a socio-medical innovation that more generally symbolized generous and goodly values within broader structures of the family, the community, and the state.

The rise of institutions for the insane can also be painted with a darker hue, however. Plans for this hospital recommended patient payments rather than straightforward charity. In addition, removing the “insane” from prisons and placing them in asylums likely freed individuals from sites of discipline, but not from strict surveillance.

To consider representation, the plate’s design depicts these interpretations of both benevolence and control. For example, the plate’s design features a fence running through the foreground, a physical boundary to keep patients contained. Indeed, viewed through a Foucauldian lens, the plate takes on a different character, one in which the “repetitive rose and leaf medallion border” can be considered not only an embellishment and the design most visible when the plate is filled with food, but also a circular cuff that restricts and retains the plate’s central image.

The plate’s aesthetics are meaningful in other ways as well, particularly as evidence of the multistage design process. The plate’s design is noticeably modified from the artist, Abel Bowen’s (1790-1850), original drawing and then line engraving, commissioned by Ridgway (see below). The original drawing includes two additional buildings, while the plate’s illustration features only the central house of the estate. The changes to the scene allow closer detail of the center building and make it stand more majestically in the frame, as the height and space of the flanking buildings would have somewhat diminished the central figure.

And while the plate’s design features only a fence running through the foreground, the drawing includes rich foliage, as well as the banks, flowing waters, and human activities of the Charles River.

And yet, the translation between drawing and plate design is not the only interrupted conversation, as Bowen’s drawing does not include details captured in the historical record. For example, the grounds’ terraced gardens, imported, rare, fruit trees, and ornamental fish pond, which could be viewed from the house when looking toward the Charles River, which cuts through the foreground, are not captured in Bowen’s account.

Such edits, additions, and cropping reveal the dynamics between reality and representation and the multiple moments of translation that occur as landscapes make their way from the viewer’s eye to the artist’s pen to the engraving plate for mass production to the transfer process, where the hands of female workers fixed the image to a plate in Staffordshire county that would then make its way back to the land where the image itself originated.

As immortalized on the plate in 1825, the “Boston Insane Hospital” stands as a transnational icon. Within the plate’s design, the estate’s central building is situated within a tranquil landscape believed to be restorative not only for the “insane,” but for all people. In this way, perhaps yet another reason that this plate was produced, purchased, cherished, and put to use at the dinner table was the therapeutic value it provided. When not being used to actually serve food, if the owner even desired to do so, this plate might have been prominently displayed as a colorful diversion and a daily dose of refined culture and natural restoration.

These are but some of the questions and potential answers one can explore when starting with the life of the object itself, a method I practiced at this CHAViC seminar and look forward to incorporating into my scholarship—to look more closely, deeply, and thoughtfully at my evidence, so that it can speak its own story.

In closing, I cannot more highly recommend my experience at the American Antiquarian Society. I encourage scholars to visit their astonishingly beautiful space (see below), correspond with their knowledgable and approachable curators, to visit their gorgeous reading room and engage with their incredible collections, and to apply for their seminars and short and long term fellowships.

Bibliography

- American Antiquarian Society. “Insane Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts).” Beauties of America: The Staffordshire Pottery of John Ridgway at the American Antiquarian Society.

- Little, Nina Fletcher. “Early Buildings of the Asylum at Charlestown, 1795-1846 Now McLean Hospital for the Mentally Ill, Belmont, Massachusetts.” Old Time New England. Vol LIX, No. 2. October-December 1968, 28-52.

- “History and Progress. McLean Hospital: A Brief History from Charlestown to Belmont.” McLean Hospital Website.

- The Transferware Collectors Club, Winterthur Museum, and Historic New England. “John & William Ridgway.” Patriotic America.