At the 2019 ASFS/AFHVS conference, I organized a panel to investigate the intersection of food studies with the fields of media studies and communication. Such collaboration sought to fruitfully expand the conceptual boundaries, theoretical and methodological considerations, and pedagogical practices of both food and media studies.

We were a group of scholars variably positioned within and across the fields of food studies, food systems, media studies, and communication, as well as at different stages of our careers, from ABD to full professor:

- Leigh Chavez Bush, Adjunct Faculty, Johnson & Wales, Denver

- Emily Contois, Assistant Professor, Department of Media Studies, University of Tulsa

- Leda Cooks, Professor, Department of Communication, University of Massachusetts Amherst

- KC Hysmith, PhD Candidate, Department of American Studies, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

- Tara Schuwerk, Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Communication & Media Studies and Program Director, Sustainable Food Systems, Stetson University

Together we endeavored to explore if and how food studies might “count” as media studies and how food is and can be explored as both medium and message. We began our panel with brief, 5-minute research presentations to present a sort of tasting flight of scholarship at this intersection. We were lucky to have live tweeters in the audience who caught some of the high points of these presentations:

We then gathered together to discuss a series of pre-circulated questions.

We began by discussing current scholarship at the intersection of food studies and media studies. We compiled a short (and by necessity incomplete) list of texts that we think provide useful models for future work, including:

Janet M. Cramer, Carlnita P. Greene, and Lynn M. Walters, Food as Communication: Communication as Food (Peter Lang, 2011).

Tisha Dejmanee, “‘Food Porn” as Postfeminist Play: Digital Femininity and the Female Body on Food Blogs,” Television & New Media 17, no. 5 (2016): 429-448.

Tisha Dejmanee (ed), “Feminism and Food Media,” Themed Commentary and Criticism Section, Feminist Media Studies 18, no. 4 (2018).

Joshua J. Frye and Michael S. Bruner, The Rhetoric of Food: Discourse, Materiality and Power (Routledge, 2013).

Katie Lebesco and Peter Naccarato, The Bloomsbury Handbook of Food and Popular Culture (Bloomsbury, 2017).

Tania Lewis & Michelle Phillipov (eds.), Special Issue: Food/Media: Eating, Cooking, and Provisioning in a Digital World, Communication Research and Practice 4, no. 3 (2018).

Signe Rousseau, Food Media: Celebrity Chefs and the Politics of Everyday Interference (Berg, 2012).

Signe Rousseau, Food and Social Media (AltaMira Press, 2012).

Next, we discussed if and how food is a medium, as well as how such a framing might prove useful for food studies research, teaching, and practice.

We began by considering the layers of media at play when it comes to food, for example: the food itself; the messages communicated on, in, and through food; and the ways that social media attaches another layer of meaning through metadata.

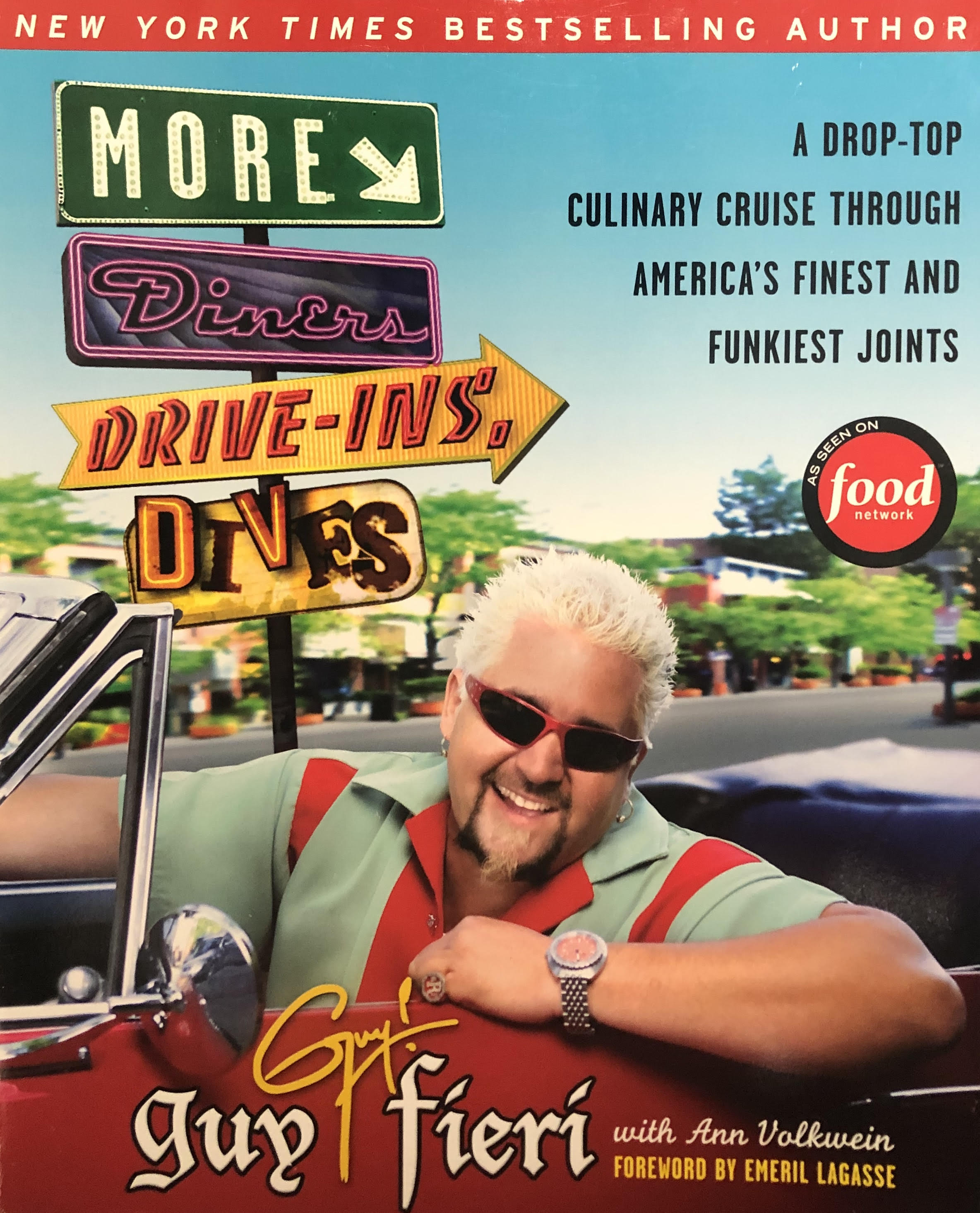

Leda asserted that cultural concepts of and standards for edibility often define the line between food and waste, as well as how this line can move depending upon space and context, all of which shapes food’s meaning. KC complicated this discussion further by considering how food media consumer demands have shaped the edible nature of food media. For example, the milk in food photography used to be glue, but now it’s “real” milk. Even if thickened with starch, its edibility remains relatively intact as a result of consumer resistance to overly and overtly “fake” representations of food. Relatedly, Leigh argued that as chefs work to create personas and opportunities on Instagram, food alone isn’t the medium, but beautiful food, the work required to make it, and all that it means beyond food alone.

We eventually decided that edibility and curation may define whether something is considered food, but no matter what, food remains a medium.

From the audience, Bob Valgenti asked us if we could imagine conditions for when food is not a medium. This required us to take a step back and more clearly define medium. I offered the broad and messy idea that media studies encapsulates everything that connects humanity, and not just to other humans. So if we think of food as a way and means of communicating, food always communicates. It always signifies; it always has semiotic meaning. It always has something to say. But if we define a medium as that which connects us, food can both include and exclude, bring us together and keep us apart. That said, connection needn’t be positive or intimate to be generative. Power is always at play. As Sarah Tracy added from the audience, hierarchy and oppression is still a form of connection.

In the end, we all agreed that the only way food wouldn’t be a medium would be if it had no meaning. So food is, always, a medium. We also discussed how the absence of food can still be read as communication and as a medium.

We next shared the main challenges we have faced researching and teaching at the intersection of food studies and media studies.

Tara shared that it can be difficult to teach food media courses when students may lack a foundational literacy in both media and food, as well as how to analyze them through categories of identity like gender, race, and class. Extending the theme of literacy, KC discussed how it can be difficult at times to find a shared understanding and set of assumptions with mentors and committee members about how and why one ought to study food media. As food studies scholars, we often have to fight to prove the worthiness of our topic, an even more complicated endeavor when studying food on and through social media.

Researching at this intersection also poses methodological challenges. KC and I discussed how the pace and breadth of food media can be exciting but exhausting to study, as the stream of posts and content never stops. Where do we draw the line for our research when our archive is always alive, moving, growing, and changing? Leda pushed us further to consider if and when we should worry about the all consuming encroachment of food media into our lives, research and otherwise.

KC, Leigh, and I also reflected upon how the method of digital ethnography blurs the anthropological boundary between insider and outsider. How much of our media life is our research and vice versa? Should we keep them separate? Why? And is that even possible? In the case of KC’s research, her own status as an influencer with more than 100,000 followers lent her an undeniable legitimacy that gave her unique access as a researcher. At the same time, it can be difficult to anonymize data when researching social media. Leigh pointed out that this can make it complicated at times to fulfill the anthropological directive to do no harm, especially when “studying up” or “sideways.”

KC shared how her research has taken her into new theoretical and methodological terrain. For example, researching hashtags used by food influencers led her to feminist technoscience and to consider the hashtag from a variety of viewpoints: linguistic, organizational, user generated, code, machine language, and as data that is coopted by users, industry, and the platforms themselves.

Both methodologically and theoretically, Leda asserted that food scholars could benefit from applying more media theory to the study of food and media. We must move beyond the study of representation to consider, for example: Hall’s theory of oppositional readings, embodiment and performance, more deeply intersectional approaches, materialism, and the relationships between the human and the nonhuman.

Leda also emphasized that media studies and communication scholars drawn to studying food tend to take qualitative rather than quantitative approaches. In her own work on food waste, much of the discussion is framed around representations of quantities of food wasted, which we need to push beyond to refocus the conversation on the entire food system.

Lastly, we shared our hopes for a future research and teaching agenda at the intersection of food studies and media studies.

Leigh grounded us in a sense of purpose, asserting that what we study ought to be something that makes life more valuable, makes it better. Our research can shed light on food media processes, both positive and negative, and pose recommendations for how to expand the positives. An activist potential must be part of this ongoing agenda. Similarly focusing on impact, KC hopes to see literacy as a key contribution of her research, as a way to help readers more deeply and critically understand food, media, women’s lives, hashtags, and so much more.

Tara pragmatically reflected that we need to think more about how to truly cross over and collaborate between food and media, particularly when we may be trained in a single, different discipline. After the completion of a PhD, how do we go about gaining a wholly new set of knowledges?

It’s here that I have great hope for the future possibilities between food and media studies. These two deeply interdisciplinary, nimble, and flexible fields pose productive invitations to one another. This post represents the product of a small group over the course of an hour and forty minutes. I sincerely hope to continue and expand this conversation in the volume preliminarily titled, You Are What You Post: Food and Instagram, which I’m co-editing with my colleague Zenia Kish and will include essays by KC and Tara from this panel. There is much to be explored at this fertile point between food studies and media studies. I’m excited for where it takes us all, together.

Top Image Credit: KC Hysmith